Controlling post-traumatic stress could be as close as a game on a cell phone

What if Soldiers could train themselves to control the physical reactions that often mark post-traumatic stress -- the racing heart, rapid breathing, and overtuned responses that make it difficult to focus on the task at hand? What if that physical control could make them feel better all around, or perhaps even help prevent PTS in the first place?

And what if Soldiers could undertake this training anytime, anywhere, through a popular game incorporated with a physical feedback system on a cell phone?

These possibilities are closer to reality than one may think, thanks to the efforts of a Vietnam veteran who is now a researcher at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C.

Dr. Carmen Russoniello's work is partially supported through Operation Re-entry North Carolina, a new ECU program that received initial funding in September 2011 from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command's Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center. This military and civilian partnership coordinates innovative research to address the rehabilitation and civilian readiness concerns of service personnel, veterans, and their families.

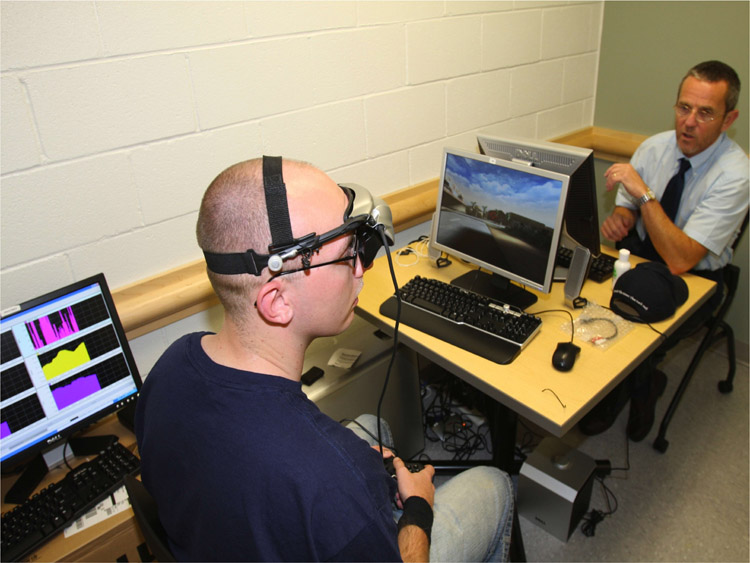

Since 2008, Russoniello has been working with Marines from the Wounded Warrior Battalion East at Camp Lejeune, N.C. He is developing biofeedback training that allows wounded Soldiers to recognize and control the symptoms of PTS and brain injury. In biofeedback, real-time physiological functions such as heart rate, breathing, brainwaves, and muscle tone are recorded and visualized to enable an individual to learn to control these functions.

Russoniello's program uses several biofeedback techniques. Marines receive neurofeedback to visualize and train their brain activity into a more focused state. And they learn to lower their heart rate through a regimented breathing process. This is combined with counseling in a graded-exposure technique that introduces greater stressors as the individual gains more control over his or her reactions.

A unique aspect of the program is that Russoniello's team has worked with Seattle-based PopCap Games to incorporate the biofeedback training into a video game.

"We had to consider how we could keep a person interested in regulating his or her heart rate," said Russoniello. "In the game, you get health points as your heart rate becomes more in sync with your breathing."

PopCap is the maker of popular mobile and social games such as Bejeweled®. A recent study published by Russoniello has linked playing Bejeweled to decreased stress and reduced depression.

Dr. Brenda Bart-Knauer coordinates Camp Lejeune projects for TATRC. She is heartened by initial results that indicate Russoniello's approach is very effective in ameliorating symptoms of PTS.

"This approach puts the Soldier back in control," she said. "He or she can learn to regulate and recalibrate that heightened state of functioning that may have been needed in a combat zone, but in fact makes it very difficult to relax and deal with everyday stress."

Russoniello recently teamed with Biocom Technologies and began two pilot projects with the new TATRC funding. TATRC sees these as important steps toward the goals of validating the results and making the program portable so service members could have access to a potentially life-changing treatment on their cell phones.

Both projects are expected to be completed in 2012.

The first is a formal study to prove that the technique of controlling heart rate variability combined with neurofeedback is effective in reducing symptoms of PTS. In a four-week graded-exposure program, Russoniello will move the volunteers from training with stressful conversation to pictures to a virtual reality Iraq combat scenario.

The second project supports work to build and test a cell phone system that records heart rate information and sends it immediately to a secure cloud server. The project incorporates a new technology developed in 2011 that turns the flash camera of a cell phone into a heart rate sensor. Place a finger on the back of the camera, and that person's pulse rate shows in the viewfinder on the front of the phone.

With the server connection, a medic in the field can send data to remote healthcare staff to assess whether an injured Soldier is in shock or going into cardiac arrest. The technology is also key in Russoniello's next goal. He is working with PopCap to incorporate biofeedback training into the game Bejeweled on a cell phone platform.

Russoniello has applied for a third Department of Defense grant to fund this work and test it in the field. The project would include training one company in a battalion using the cell phone game before and during deployment, and simultaneously following a second comparison company to determine whether or not the training can prevent PTS. He hopes to have the adapted game and funding in place to begin the study sometime during 2012.

"Evidence indicates that controlling the physical response can impact one's mental experience of stress," says Russoniello. "This probably goes back to our deepest survival instincts. When a person has an internal feeling of safety and physical harmony, rather than turmoil, the cognitive part follows along."

He adds, "It's exciting that we may have a game that could make an impact on PTS with little to no side effects. I would love to see this proven and in use for our service members within the next three years."

For more information, visit

ecu.edu/biofeedback or

tatrc.org

or

tatrc.org .

.

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.