Brain Health in Spotlight as TBI Researchers Stake New Ground at 2019 MHSRS

After a marathon three-hour session on traumatic brain injury (TBI) at the 2019 Military Health System Research Symposium in Kissimmee, Florida, the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command's J.B. Phillips picked through his notes in an effort to boil-down the details.

"There's a lot to be excited about," said Phillips, Program Manager for the Neurotrauma and TBI Portfolio at the USAMRDC's Combat Casualty Care Research Program. "We've got excellent data coming forward using saliva and blood as possible pieces to this puzzle."

The puzzle Phillips is referring to is, of course, TBI as a whole; that massive and often-amorphous monster the DOD has been grappling with in earnest over the past two decades. According to the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, more than 383,000 Service Members have been diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury since the year 2000, making emerging research into the causes, effects, and parameters of TBI a top priority –and an equally hot commodity– within the military medical research community.

"We've advanced to the point now where prognosis of TBI is at the level of concussion," said Phillips, "and we've also got two approved biomarkers to aid in computer tomography (CT) referral."

In short, that means researchers now have a pair of biomarkers –which are, essentially, measurable indicators of the presence of a disease– to help guide computer imaging of the brain. Ultimately, that means scientists now have approved parameters for certain types of head injuries – a huge win by all accounts. Now, all that's left is to fill in are the –still relatively sizable– blanks.

Jessica Gill, a clinical researcher at the National Institutes of Health, wants to move that relatively fresh achievement in biomarker science even further down the field, translating military work into the public sphere by determining when, exactly, to allow young athletes impacted by head injuries back onto the field.

"Up to 80 percent of Americans will receive a concussion over the course of their lifetime," said Gill during her presentation. "And to me, that really cements the fact that we need an objective biomarker for ‘return to play' concepts."

To that same end, and with a similar test group –young athletes– Los Angeles-based data scientist Corey Thibeault found that male athletes reported much milder symptoms as a result of the same general type of TBI than females; an issue he described as problem for the future of research into the subject. According to Thibeault, variables such as age and physical growth are also issues moving forward.

"We assume individuals and their injuries are heterogeneous," he said, "but we have to consider how they change over time."

Other presenters at the TBI-centric session focused on a variety of other efforts and achievements within the field. Research into the relation of the blood-brain barrier –or, the semi-porous barrier that separates the blood from the brain– to the neurologic issues following a TBI were highlighted near the top of the session, along with research efforts by the USAMRDC-funded Transforming Clinical Knowledge in Traumatic Brain Injury Network (TRACK-TBI) spearheaded by the University of California, San Francisco. Further, and as always, attendees were eager to entertain news on emerging technologies promising a non-invasive pathway to gauge TBI severity.

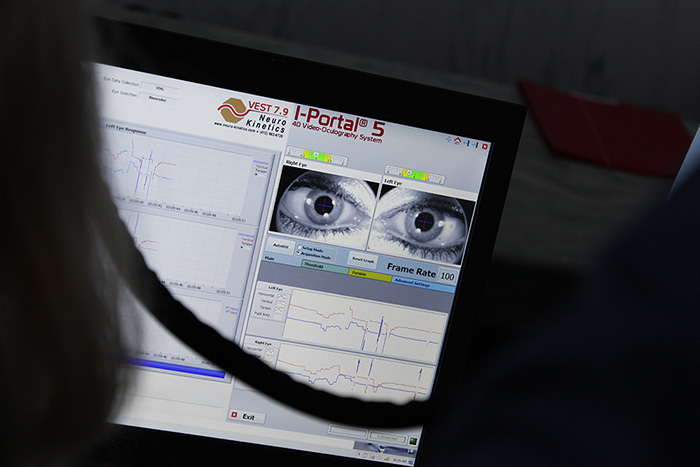

"A lot of exciting things are happening with fluid-based biomarkers, sure," said Nsini Umoh, Assistant Program Manager for the CCCRP's Neurotrauma and TBI Portfolio, "but advancements in neuroimaging are big as well."

Yet a single, one-size-fits-all solution for all instances of TBI remains elusive – and will forever, perhaps. Regardless, experts say the path forward is becoming clearer by the day, the month, and the year. Indeed, by teaming measurable progress in blood and biomarker-based research, along with emerging technological research, perhaps the day will come when the public will be able to see and feel the benefits of TBI research in their own lives – no translation required.

"It's a lot to sift through," said Phillips, "but it's very real."

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.