Touting New Patent, Future of Warfighter Eye Care Arrives at USAMRICD

Timothy Varney had been waiting nearly seven years for some good news, and when he finally got it on the afternoon of October 15 – he almost threw it away.

"I saw this piece of junk mail," says Varney, a research biologist at the USAMRDC's U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense (USAMRICD) in northeast Maryland. "Honestly, I just thought some company wanted to sell me something."

Turns out the letter was from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, which was alerting Varney that he'd finally won official U.S. patent protection for his new invention: a device designed to help restore vision to Soldiers suffering from severe eye injuries. Dubbed IsoMate for now, the tool – which has a wide range of potential public health uses as well – is designed specifically to aid those impacted by chemical warfare agents like mustard gas.

"It's hard to explain what mustard gas does to a person at a molecular level," says Varney. "When people are exposed to mustard gas, the eyes are the first to show complications. You always hear about the skin, but it's the eye, too."

To that end, Varney and his team initially began researching ways to heal chemically-affected eyes – human corneas, specifically – back in 2012. Yet to describe the function of his invention first demands a description of the eye as an organ; how it's structured, how it works, and how IsoMate can ultimately help following injury.

In short, the human cornea (the front part of the eye that covers the iris) consists of three individual layers which are, altogether, barely a half-millimeter thick. The layer closest to the iris is comprised of corneal endothelial cells (CECs), which look – under a microscope, at least – like a bunch of tiny hexagons. As a person ages, they naturally begin to lose these CECs. "Gaps start to appear in between those hexagons," says Varney, noting that a similar biological progression of CEC loss occurs following a mustard gas attack.

As such, the key to restoring vision is to supply more CECs to the eye, as their chief function is to pump water out of the cornea (a process which improves optical clarity) and then also to pump much-needed nutrients into the cornea.

That's where things get tricky.

Growing additional CECs in a lab is tough but not impossible, but you've got to separate the thin CEC layer from the thick, fibrous middle stromal layer of the cornea before you can do so. In order to do that, you've got to scrape the out the CECs with a sharp tool, a process which often results in the accidental scraping of stromal cells as well; a mingling of different layers that ruins your culture and forces you to start all over again ("Those stromal cells grow like weeds," says Varney, "much faster than CECs.").

Enter the IsoMate.

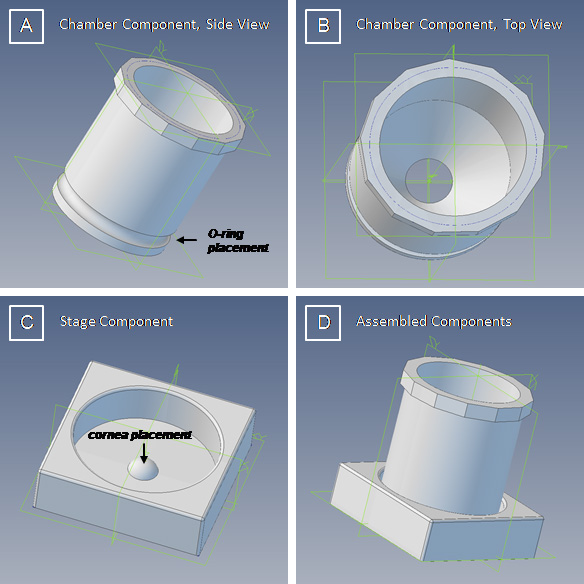

The device, which is created by a 3D printer due to its tiny and exacting technical requirements, resembles a pushbutton placed atop a square box. Following the surgical removal of the cornea, the IsoMate takes that cornea and places it on top of the pushbutton section, flipping it inside-out so the CEC side is exposed. Scientists then use a pair of different enzymes to chemically separate the layers from each other before finally using a pipette (which is an eyedropper-like tool) to vacuum out the CECs. The whole process is far gentler than the previous scraping method, and as such prevents any mingling of the CEC and stromal layers. Following the procedure, CECs can then be grown in a lab and finally transplanted back into the eye to help restore proper vision.

"With this tool," says Varney," we can take out what's bad, and put in what's good."

The procedure is landmark because, currently, no medicinal treatment exists to combat the effects of mustard gas exposure. And while corneal transplants are a potential solution, the supply of corneas suitable for medical use is limited. Too often, a healthy cornea is not available at the time a patient needs one, according to Varney.

Outside of military applications, the IsoMate tool has a number of potential public health uses as well. One of those, according to Varney, is to help remedy cataract surgeries that aren't successful on the initial pass. The device could also be used to combat Fuchs' dystrophy, a genetic disease in which the CEC layer of the cornea undergoes severe degenerative changes. As such, Varney and his USAMRICD team (which has included, over the years, a total of six Soldiers and one student) are accelerating their testing schedule by employing animal models in order to create supporting evidence that shows their new method works. To that end, Varney and his team are also searching for industry partners to help in manufacturing and awareness efforts.

"It makes it worth it," says Varney of the long road to achievement. "We're not clock-watchers around here – I mean, this is why we come to the office and do this every day."

Not bad for an accomplishment that – quite literally – almost wound up in the trash.

Says Varney, "When I see people in uniform, I think about the chances they could be deployed soon – and we want the best that Army medicine can offer if they need it."

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.