Army Shines Light on Health, Care of Military Working Dogs

Like most people at the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command's U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research, Lt. Col. Emilee Venn is laser-focused on one, single thing: the health and welfare of the Warfighter. However, as USAISR's Chief of Veterinary Clinical Operations, Venn is also concerned with the treatment and care of Military Working Dogs. Given the increased role such animals have assumed in recent years – most notably in deployed environments – their specific medical needs have become increasingly important as well.

"The best way to think about it is – wherever our people go, the dogs are right there with them," says Venn, noting that there are slightly more than 1,800 active-duty MWDs across the globe. "Or perhaps more simply, the dogs go where the people go."

Venn's recent speaking engagement at the American Academy of Emergency Medicine's 28th Annual Scientific Assembly in Baltimore, Maryland highlights the growing profile of military veterinary medicine within the larger U.S. medical community. Her presentation, "Canine Combat Casualty Care: Battlefield Medicine for MWDs", served as a platform to discuss both the impacts and benefits of military veterinary research and how those principles can be translated across both the Department of Defense and the civilian world, too.

"It's a really exciting time right now for the canine aspect of combat casualty care," says Venn, a small animal emergency critical care specialist veterinarian by trade who's served in the Army for the past 15 years. "We're following medical research from the human side of things in that we're focused on data-driven, evidence-based operation – and we're also making sure dogs are also considered in these high-level approaches to minimizing preventable deaths on the battlefield."

Only recently has the military medical community begun the process of appraising data extracted from 20 years of animal-involved combat situations gathered from both Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. According to the Defense Health Agency, more than four thousand MWDs suffered injuries in combat over the past two decades. That data sits at the crux of Venn's work – and is the basis for current efforts by Veterinary Services personnel to research and prepare for the proper treatment of canine combat causalities. Recently, the Army has made substantial investments in medical infrastructure for MWDs. In January, DHA launched the Joint Trauma System Military Working Dog Trauma Registry, which is designed to serve as the kind of expansive central data repository that Venn and others have long hoped for.

The biological differences, of course, dictate the need for such a database – and also for varying approaches in protocol. For instance, while Venn notes that dogs are historically much easier to intubate than humans, dogs are far more resistant to opioids – so they in turn require a higher medication dosage, generally. Further, when it comes to MWD medical care, Soldiers must take care to properly restrain the animal before attempting an intervention – a simple yet occasionally overlooked step in the process ("We don't want someone responding to the injured animal to get injured themselves," says Venn.). Also notable when it comes to animal care: in cases of traumatic bleeding, a basic Combat Application Tourniquet will not fit a MWD due to structural differences in anatomy; therefore a more elastic, compressive tool (like a SWAT-T tourniquet, which is essentially a rubber dressing that can be wrapped tightly around a wound) may work better.

Additionally, as part of the aforementioned Army investment, a Canine Tactical Combat Casualty Care card (or, "cTCCC" card) has been developed for the purposes of documenting injuries anywhere a canine is deployed in support of DOD operations. The cards can be filled out by the handler or provider who tends to the canine; then, following the resulting medical treatment, can be handed off to the nearest supporting veterinary unit to be uploaded into the larger system.

"The Veterinary Corps is a small part of the Army; we can't be everywhere," says Venn. "So to extend our reach we try to help train and get people comfortable with a scenario where if a dog does come into your station, you know a few key things to care for that animal until they can get to a veterinary asset."

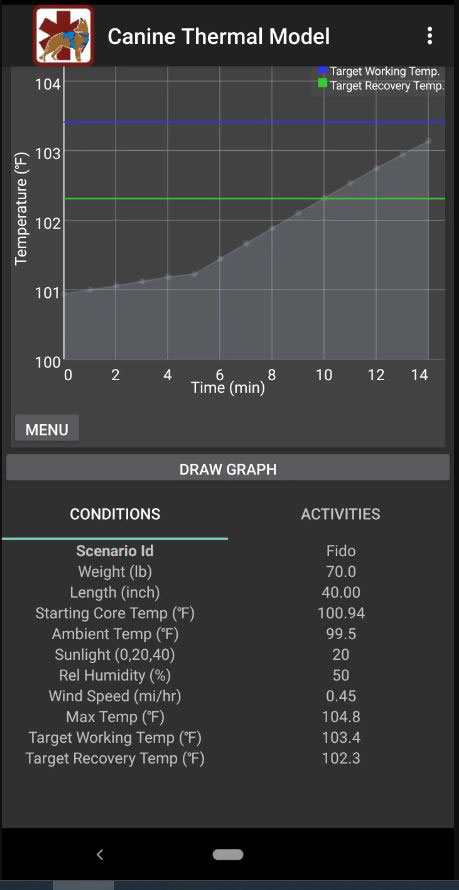

Investments are underway across other parts of the command as well. At USAMRDC's Medical Materiel Development Agency, a technology designed to reduce heat injuries to MWDs in operational environments in currently in the acquisition pipeline. The Canine Thermal Model Planner is a smartphone application based on an algorithm originally developed at USAMRDC's Research Institute of Environmental Medicine. By entering an MWD's vital statistics – like body mass, core temperature, etc. – into the app, the CTMM can provide a handler with guidance on the appropriate work/rest cycles required to keep the MWD in top condition. According to Gail Wolcott, product manager at USAMMDA, the app – which is currently available to the military community – will likely soon be paired with an accompanying collar outfitted with sensors that will track movements in real-time, providing even greater feedback to the handler.

"This is a low-cost, fast-turn, noninvasive product that can be used to help mitigate injuries in MWDs," says Wolcott, who envisions the CTMM collar to be available for use in MWDs by late next year.

Venn points out the U.S. civilian sector is increasingly focused on the health and welfare of operational canines, notably due to their routine use in first responder situations; specifically in police and fire emergencies. The uptick in civilian use of working animals is why she was tapped to make her presentation in Baltimore in the first place.

"There are certain things we've learned in dealing with cases of canine trauma on the battlefield – situations that could potentially equate to what EMS personnel or a paramedic might see if they're responding to a scene and there's a law enforcement K-9 that's been injured," says Venn, noting the translation of military battlefield care to a civilian setting. "We want those people to know how to spot the things that are going to put that animal at risk within the first ten minutes."

Moving forward, Venn notes several other canine combat casualty care projects currently taking place throughout the Army. Just recently the Army and DHA approved funding for studying the development and application of potential canine plasma products, as well as a retrospective study on the causes of mortality in canine trauma; other, similar projects are taking place as well. For Venn, such efforts represent the best of both worlds: not only is the Army granting her even more and greater resources to do what she does best, but she's also advancing the knowledge required to save future generations of MWDs.

"There's been a lot of work done in the past few years to move these big rocks up the hill," she says, "but there's still a lot more to do."